At the recent June Sydney Go Meetup there was a small debate on reference types in Go, in particular, whether a function is a ref. type. See the Functions section below, where I show that a func (closure) is a ref. type.

Then there is the whole debate on whether Go even has reference types. I don’t really want to get into that as the discussion seems to generate more heat than light.

The important thing is to understand how reference types (or whatever you want to call them) work.

(But for those who insist that Go does not have reference variables I show in Captured Variables below that even using the strictest definition Go does have them.)

Background

General

The idea of reference types (as opposed to value types) goes back to Fortran. Though, now I think about it, even assembly languages have addressing modes that are “reference types” – where a value (register) is used as a memory address (reference/pointer). This contrasts with “immediate addressing”, where there is no memory address just a value.

Fortran

In Fortran, when you pass a variable as an argument to a function (subroutine), the address of the variable is placed on the stack. When the function makes use of the parameter it is actually working with the original variable (perhaps with a different name), and dereferencing it through the address.

This way of passing parameters came to be called “pass-by-reference”. It was error-prone, resulting in bugs - for example, if a parameter was assumed to be just an “input” parameter but was (deliberately or inadvertently) modified, it could have bewildering consequences.

Algol

When Algol appeared a few years later they avoided this problem by making parameters “pass-by-value” (by default). Note that Algol also allows pass-by-reference in case you wanted to return a value, or for efficiency if you wanted to pass a large object. (I think Algol also has pointers as in C - see next.)

C

C is derived from Algol - so uses “value” types. It does not have pass by reference, but you achieve the same effect by taking the address of a variable (using the & operator).

In this way, C is much more like assembly, a pointer is an address – you must explicitly dereference it (using the * operator). This makes things more obvious than the implicit dereferencing of other languages.

Note that types in C have some “optimizations” (because passing large objects on the stack is inefficient). First, whenever you use an array in C you get a pointer to the first element. Also, originally in C you could not pass a struct to a function - only a pointer to it - though this restriction was later lifted.

Java

Java introduced (or popularised) the idea of a reference type (as opposed to just passing by reference). In fact, just about all variables are references (addresses on the heap) in Java.

A purist might claim that use of a reference type must be indistinguishable from the use of a value type. In Java, the so-called reference types can take the value null - making them more akin to pointers.

C++

C++ is (effectively) a superset of C, so it has pointers. However, to facilitate other features that were added to C++ it also added reference types. A reference type is just an alias to an existing variable. Internally it’s a pointer to an actual value – so you can’t have a null reference, and you don’t need to use the * operator to use the value.

Go

Go, like C, is said to be value based. You can use pointers for “explicit” references.

But Go has the complication that there are a few types that have “hidden” pointers. For example, internally maps are just pointers, and slices contain pointers, but it is easy to forget this as you don’t need to explicitly dereference the pointer.

For this reason, emphasizing that these types are reference types can be useful as a reminder to take care. Unfortunately, there are a few different ideas about what “reference types” actually means.

Definitions

I have created a list of definitions I have found in various places. (Some of these I had to insinuate from various discussions.)

- Go does not have reference types

- Any Go type that has a hidden pointer

- Any type that can be assigned

nil - Any type that can be created using

make - Slice, map, channel, function, pointer

- Slice, map, channel, interface, function

- Slice, map, channel, interface

- Slice, map, channel, function

- Any above + structs, arrays, or interfaces that contain them

- Anything that needs “deep” copy/compare

Note that when I talk about a function I mean the func type, which is officially called a closure.

What’s the best definition?

We can discount definition 1, as the string type has a hidden pointer. Strings are immutable, so you can’t modify the string through the pointer. Hence string behaviour is effectively indistinguishable from other primitive types.

Similarly, definition 2 does not work as interfaces are not reference types. Like strings, interface values are immutable (unless they contain a reference type, and you use definition 8).

Definition 3 is also wrong as, pointers and func types are reference types.

I am using definition 4, since it satisfies my steps for determining if a type is a reference type.

My Steps

The problem we are trying to highlight is that you can copy a variable then inadvertently modify the original when you only think you are only modifying the copy.

So I will use these steps to determine if a type is a reference type in Go.

- Declare variables,

aandb, of the type - Create/modify

ain some way - Assign

atob - Modify

bin a different way - Check if there is a discernible difference in

a

What are they?

The Background->Go section above goes into detail on how I define “reference” variables.

In brief, if you assign a variable to another variable changes in either will be seen in both. Indeed, it is this behaviour that has lead to many bugs.

The important thing is to understand how they work, not what you call them.

For example, I recently discovered a bug in my own code which caused a data race. This happened because I passed a map to a different go-routine (through a channel) rather than cloning it first. This is a common sort of mistake in Go, and the sort of thing I would not have done in C.

So let’s look at how different “reference” types work. I’ll also look at arrays (and interfaces), even though they are “value” types.

Slices

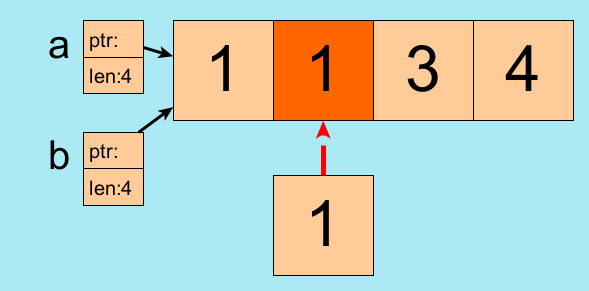

The following code demonstrates that slices are reference types.

var a, b []int

a = []int{1, 2, 3, 4}

b = a

b[1] = 1

log.Println(a) // [1 1 3 4]

Remember that even though the contents of a can be modified using b, you can’t change the length or capacity of a using b (or indeed, change the underlying array that a points to). Perhaps you should think of slices as “partial” reference types.

Note: This diagram does not show the capacity of the slices. Both slices have a capacity the same as the length (4).

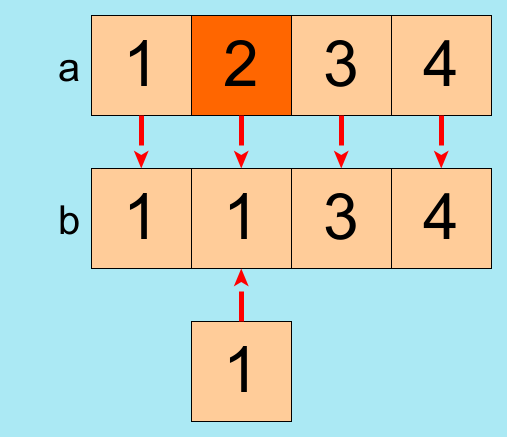

Arrays *

a := [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4}

b := a

b[1] = 1

log.Println(a) // [1 2 3 4]

Arrays are often expected to be reference types (probably because of how they work in C) but are value types not reference types.

When you use an array you get a complete copy of it.

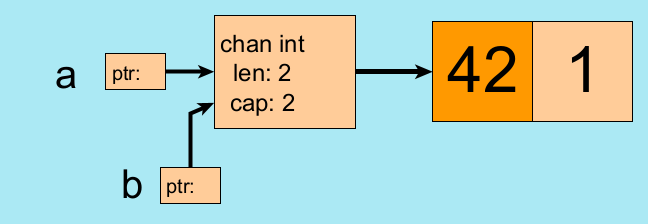

Channels

a := make(chan int, 2)

b := a

b <- 42

a <- 1

log.Println(<-a) // 42

Although it is not usually a source of bugs, channels are reference types.

Maps

a := map[int]string{1: "one"}

b := a

b[1] = "42"

log.Println(a) // map[1:42]

As you guessed, maps are reference types in much the same ways as channels. Just about all Gophers encounter problems due to this at some point.

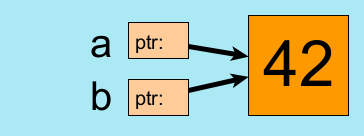

Pointers

Pointers are reference types.

var a, b *int

n := 1

a = &n

b = a

*b = 42

log.Println(*a) // 42

Some argue that they are not references types because you must explicitly dereference the pointed to value (using the * operator) - but this is similar to accessing the values of a map or slice (using the indexing [] operation).

Functions

The following code shows that a closure is a reference type since the value m is shared between a and b

type myInt int

func (m *myInt) f() int {

*m++

return int(*m)

}

func main() {

var a, b func() int

m := myInt(1)

a = m.f

b = a

b()

log.Println(a()) // 3

}

If closures were value types, the code would print 2 not 3.

Interfaces *

Despite claims to the contrary, interfaces are not reference types, otherwise the following code would print 42.

var a, b interface{}

a = 1

b = a

b = 42

log.Println(a) // 1

Composite Types

Composite types are types composed of other types (ie, anything apart from the primitive types - numerics, bool and string). Even composite types that are normally value types, can act like reference types if they contain a reference type.

type sp struct { p *int }

n := 1

a := sp{p: &n}

b := a

*b.p = 42

log.Println(*a.p) // 42

Arrays, structs and interfaces if they contain a reference, are also reference types, according to my definition.

Does Go even have Reference Types?

As pointed out at There Are No Reference Types in Go the concept of reference type does not appear in the spec. (since 2013).

Even Dave Cheney says “Go does not have reference variables” at There is no pass-by-reference in Go.

My opinion, without getting into pendantic semantics™ is that the idea (as discussed above), is useful, at the very least as a reminder to take care when copying maps.

However, even with the strictest definition of a reference, Go does indeed have them when a closure “captures” a variable.

The strictest definition is, as in C++, that a reference is just an alias to an existing variable. Note that even reference types in Java fail this definition, since they can be null.

Captured Variables

Here is an example of Go code with a reference variable.

i := 1

func() {

log.Println(i)

}()

On the 1st line, we create an integer variable i. Then we use i (on the 3rd line), but this is not the same variable, even though it has the same name and references the same value.

The func (starting on the 2nd line) is a closure that captures i by taking its address. Any use of i in the function is by reference to the original i.

Here’s a complete example, which shows that i within the closure continues to exist after ff() returns and the original i is no longer in scope.

func ff() func() {

i := 1

return func() {

log.Println(i)

}

}

func main() {

f := ff()

f() // 1

}

The value is still available when f() is called at the end of main(), as the compiler determines (with escape analysis) that it is needs to be placed on the heap.

Deep Operations

While we are on the subject, I just want to explain what is meant by “deep” operations such as deep copy and deep compare.

In Go, when you copy pointers (eg using = etc) or compare pointers (eg using ==) you are just using the pointer values. That is, you are only copying/comparing the memory address (the pointer’s value), not the values pointed to.

This is called shallow copying/comparing. To use the values you must “dereference” the pointer, for a deep operation.

For example, if two pointers point to different variables, they will not be equal, even if the variables pointed to have the same value.

n, m := 1, 1

p, q := &n, &m

log.Println(p == q) // false (shallow compare)

log.Println(*p == *q) // true (deep compare)

Because Go is a “value-based” language, when you copy (by assignment, passing a parameter, etc) or compare (using ==, etc) the compiler uses “shallow” operations.

In order to perform deep operations on “reference” types you generally need to code it “by hand” or call a function. Let’s look at how…

Maps

You need to manually provide deep operations on maps, such as using a loop to copy elements.

Note that Go 1.21 (just released - see Go 1.21) provides generic helper functions in the maps package: maps.Copy and maps.Clone to copy a map, and maps.Equal, etc to compare maps of the same type.

Slices

The built-in copy function allows you to copy the contents of slices, but this will not change the length of the destination slice.

To get an exact copy of a slice you must create a new slice (with the same length and capacity) then copy over all the elements using a for ... range loop. This gives a deeper copy but if does not recurse deep into the slice contents - such as if the elements were pointers, slices, etc.

Deep comparison of slices is typically done manually, though the standard library does provide bytes.Equal for comparing byte slices.

Note: like for maps, Go 1.21 provides generic helpers: slices.Clone, slices.Equal, etc.

Pointers

As we saw above, use the * operator for deep(er) operations.

Channel, Function

It’s not possible (or generally useful) to perform deep operations on these types.

Composite Types

Deep operations on these types are only necessary if they contain “reference” types. In this case you need to manually code deep operations (also see reflect.DeepEqual below).

Since composite types may nest other composite types (to any depth), you can have more than one level of depth in the “tree” of relationships. Deep means traversing all the levels for a deep copy or deep comparison.

Standard Library Functions

As mentioned there is a bytes.Equal function for comparing values of type []byte. It returns true if the slices have the same length and contents but ignores capacity.

The standard library also provides reflect.DeepEqual which usually works well for performing a deep comparison. Since it uses reflection it may not be as efficient as a coded comparison, or a generic one. It can also give strange results for unusual types.

With the advent of generics, the Go authors have created generic functions to perform deeper operations on maps and slices. Note that the elements themselves are “shallow” copied/compared - ie there is no recursive “depth” as with reflect.DeepEqual.

See the Copy, Clone, Equal, Compare, etc functions in maps and slices packages. These generic maps and slices packages have now been added to the Go standard library in Go 1.21.

Comparability and Map Keys

The behaviour of “reference” types has lead to other behaviours of the Go language that can seem strange until you understand the reasons.

For example, the rules for comparability (use of == and != operators) can seem inconsistent. Why can you compare channels but not maps?

Map Keys

From what I can gather, a lot of Go’s inconsistent rules come down to the problem of making sure that you can’t break maps.

Maps rely on their key values comparing consistently. For example, to get back an element you added to a map the key value you supply must always compare equal to the key value you used to add the element.

If a key value changes (such that it no longer compares the same to other key values) then it can result in very strange behaviour. (I’ve encountered this problem with maps, and their ilk, in C++.)

Map keys are the main reason for the comparability rules of Go.

// Invalid map keys - *** NOT VALID Go ***

var a map[[]int]string // slices are not comparable

var b map[func()]sring // funcs are not comparable

var c map[map[int]bool]string // maps are not comparable

var d map[chan int]string // OK (chans are comparable)

Comparability

If you are not familiar with the comparability rules of Go then as brief simplification: there are three types that may not be compared: maps, slices and functions. Moreover, structs, arrays, and interfaces that contain them, are also not comparable.

Ostensibly this is because they are “reference” types. But then why are pointers and channels comparable?

I think it’s because it would be confusing if comparing slices and maps did not compare their “contents”. Comparing pointers and channels is less common or less likely to cause confusion.

I was going to explore this in depth, but I’m getting side-tracked. It would be wordy to explain it thoroughly and this post is long enough - maybe later.

Conclusion

I hope this was a useful explanation of how types with internal pointers work. This is what many people mean when they talk about “reference” types in Go.

To avoid problems the main points to remember are:

- slices always have an underlying array (or are nil)

- a slice’s underlying array may be shared - changing slice contents changes the array, and any sharing slices

- when you assign a map (or pass it as a parameter) you are not getting a copy of the contents

Comments